Wolfram Knöchel: In the Medoc in search of clues (2)

The author of these letters is no longer with us. He almost never spoke about those times. I only know tiny shreds of his memories, shards of light, sometimes appearing on the edge of irrelevance, which might have triggered remembrance. One could not call them stories really, most of them without a happy end. When he noticed it, he changed his mind quickly and carried on with the banalities of life, almost like he regretted that the memories had slipped his mind. The collective silence of a generation of German men.

On the rare occasion of an outburst, his face expressed only disdain ...What did my father experience? What is beyond the imagination of his descendants who never made that experience? Why did he fall silent, later, as the wounds were healed? Were they ever healed?

The names of the places are like a melody: St. Medard-en-Jalles, Soulac-sur-mer, St. Vivien… almost like a French chanson. One can barely understand them, but they sound so sweet. Le Pin-sec, the dry pine tree, it could be the name of an old Inn with grey shutters and a wooden veranda, where the sand of the dunes made little waves…

The internet tells me a different story. My little quaint Inn, in reality it is a huge camp site on the Atlantic. Faceless resorts, rows of a run-down trailer park.

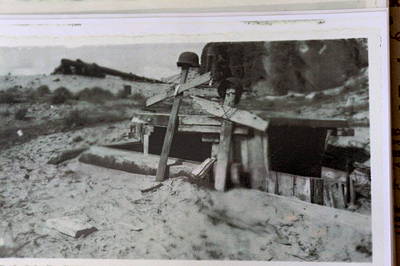

That disappointment confirmed my resolution – I want to go to all the places. I want to see with my own eyes, where my father wrote these letters, behind barbed wire fences, the sand everywhere, the tempestuous Atlantic in a Biscay storm and he writes himself away from a reality, which was his prison, his school and his home in the last 32 month.

When I am reading the letters I can feel his outrage at the deprivation of his liberty. The boy with the distinctive sense of justice had to accept that there was no such thing as justice. Asking ‘Why me?’

Of course there is a responsibility. ‘We are tidying up here, we can’t go home before it’s done, can we?’ A sense of guilt, atonement, unacknowledged though, play a part.

I am not sure what is real, I only know his accounts. I have his letters and I don’t know what was his reality, his struggle to make the unbearable bearable for himself and his parents. His efforts later in life to turn the despicable into strength, an effort that had to be learnt by millions, just to survive, to fit in into the new system. CV’s in the course of times. In it, the barbed wired time was running out, more and more into insignificance. Did it really?

He could not know, then, that there would be a little pencil mark in his personnel file all through his working life. Caused by his captivity on the wrong side, not the Russian side, no - the side if the class enemy. That needed some explanation. That stain could even be found in files of some of the members of the politburo: allied captivity – only the ones who sang the hymns of the new ideology the loudest, recovered. Just.

My father spoke about that pencil mark only after the system after the next but one collapsed. A collapse I could witness myself. In those days, in 1990, I had lots of questions for him, fierce questions, reproachful questions. But more about the times after the barbed wire, the years before remained unexplained although some of the answers might have been found there as to where the silence began, why it began?

Raising these questions today I am always met by a knowing nod, all seems clear to them. Understandably they didn’t want to hear about it anymore, about the war. They wanted to forget. Did they really want to forget it or was it just the better way for everyone? Did we really not ask about it, because we didn’t want to know and the world remained in order? Good or bad had their place, the question of guilt was answered, and we in the east were ‘on the right side‘, the side of the winner anyway?

Behind the barbed wire fence my father wasn’t ‘on the right side‘. In life afterwards he didn’t really wanted to be ‘on the right side‘ either. Or did he want it more than ever? In his rare revelations the time in captivity never became more heroic than it actually was and sometimes even signs of what could be, forgetting the circumstances, called a normal life flared up. Women, a black whore was teaching him love in a brothel in Bordeaux, where the he, the prisoner, would normally scrub the floor.

As a young girl I could smell adventure in the little stories, envied him who had seen the world. A world I was locked away from. I didn’t know anything about the fact that even there only the lowest of the low shared their common experiences – the POW and the black whore.

Then there is my middle name, Yvonne, which made my father telling me about this woman. His first love behind the barbed wire. In my fantasy she is absolutely handsome. Her copper red hair frames her face in big waves. Porcelain skin. Her father owned the local pharmacy, his son - already fallen as a soldier. All seemed fine. Then the camp was relocated, nobody knows where to. Grief-stricken Yvonne is trying to commit suicide. 10 years later I was born and I was named after her.

Nothing of it can be found in those letters. This is not something a son writes to his parents. And there are so many other things unwritten too. That’s why I’m looking for answers. I am going to France, to the Medoc.

In the months before my journey I am trying to make allies. I find a French woman, a historian, who dedicates her time to research the difficult subject of of

the French-German relationship. I meet German and French people, via email first, later in person, who voluntarily want to help me with my quest, despite the

fact that there are hardly any contemporaries left.

In the months before my journey I am trying to make allies. I find a French woman, a historian, who dedicates her time to research the difficult subject of of

the French-German relationship. I meet German and French people, via email first, later in person, who voluntarily want to help me with my quest, despite the

fact that there are hardly any contemporaries left.

The Chinese whispers works. I am getting emails from total strangers who have heard of my research like Christian Buettner. He found out about it in the German consulate in Bordeaux and he brings me together with contemporary witnesses in Vivien-sur-mer and Le Verdon.

He and his partner, Ms Elke Schwichtenberg, they not only convey to us, who we are voyagers, the impression of the life in Medoc now and then, but also about the mentality of the locals and of all the Germans who stayed and became locals. I owe it to them, that I could spend an unforgettable morning in the front room of Roger Armagnac, the old seafarer of Le Verdon who willingly showed us his collection of old photographs of that time and who answered my many questions and who also not only explains the dangerous shallow waters between the Gironde estuary and the Bay of Biscay, but shares with me his great life experience and one simple historic truth: There will always be good people and not so good people regardless of the nationality they belong to.

My worries that even though seven decades have past, I would still be met with resentment, here where German megalomania was forced into the sand dunes, they all disappeared when I looked into the friendly eyes of Roger Armanac. (Although I have to say that I will never share his enthusiasm about the achievements of German military technology like Big Berta – a sort of heavy siege gun. I’d rather listen to his profound explanation that to protect the beautiful lemon trees in his garden from scale, he puts up little bags with crushed eggshells.)

Christian and Elke also take us to Madame Jeanne Baudray, the longstanding Mayor of St. Vivian, and one can’t deny that, despite her old age, she has developed

a clear view on the necessities of our world – whether during the Resistance movement as a seventeen year old or later in life.

An unexpected chapter in my search for clues was brought up by Sieghild Jensen-Roth. She lives in St. Medard-en Jalles for many years and she tells me, that

because of the research for my project, she sees her hometown in a completely different light. The gym where she regularly exercises, turns out to be that part

of the group of buildings that was formerly the POW camp. And also it looks like the puzzle about the the daughter of the pharmacist can be solved here, as far

as it is possible with the distance of all the decades. As luck would have it the subject attracts the attention of the historian Madame Arlette Capdepuy who is

doing a research project at the Université Montaigne Bordeaux where a part of it is about the German Demineurs.

Christian and Elke also take us to Madame Jeanne Baudray, the longstanding Mayor of St. Vivian, and one can’t deny that, despite her old age, she has developed

a clear view on the necessities of our world – whether during the Resistance movement as a seventeen year old or later in life.

An unexpected chapter in my search for clues was brought up by Sieghild Jensen-Roth. She lives in St. Medard-en Jalles for many years and she tells me, that

because of the research for my project, she sees her hometown in a completely different light. The gym where she regularly exercises, turns out to be that part

of the group of buildings that was formerly the POW camp. And also it looks like the puzzle about the the daughter of the pharmacist can be solved here, as far

as it is possible with the distance of all the decades. As luck would have it the subject attracts the attention of the historian Madame Arlette Capdepuy who is

doing a research project at the Université Montaigne Bordeaux where a part of it is about the German Demineurs.

We all meet in the Archives départementales de la Gironde and I experience something completely unexpected: huge interest and sincere thanks for the letters which are a valuable report of times of which even in French archives little or nothing can be found. The letters are now part of the archive and can be used for scientific research. They are supposed to be used also for interdisciplinary projects developed for German and History lessons for the French sixth form. All with the help of letters from somebody who was only slightly older than them students seventy years ago.

In the meantime I have contacted the Francke Foundation in Halle/S. and they are planning to do the same interdisciplinary project as the French soon as next year. About the alumnus Wolfgang Knoechel, who became a POW and a Demineur.

All the adventures and encounters throughout this impressive journey will be incorporated in a book together with the letters and it will be released at the Leipzig Book Fair in 2016. Around the same time I will produce a radio feature for the Mitteldeutsche Rundfunk (MDR) about this exciting French-German project, where so many habitants of the Medoc participated. To all of them I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude.

I am also grateful that nobody asks what could possibly be important or interesting this subject today – 70 years later.

2018 Karin Scherf (Halle), translation: Betty Bokel